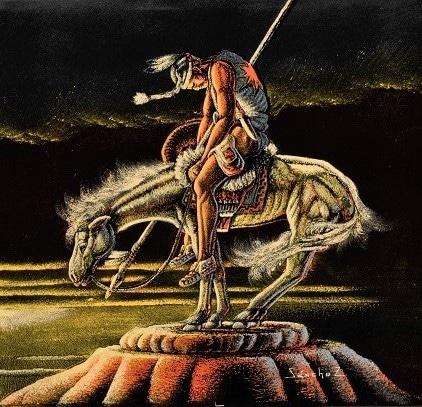

The End of the Trail, as a sculpture or image, is one of the most recognizable symbols of Native Americans in the United States. The lone, weary warrior slumped across his equally tired horse is frozen in time. This image of the Native American’s struggle against westward expansion has become so renown it was often recreated by traveling shows and rodeos.

About the Artist

James Earle Fraser (1876-1953) was an American-born artist who grew up on the plains of Mitchell, South Dakota. As a youngster, he witnessed the pioneers and hunters of the time and heard the stories of the decline of the Native Americans and the confiscation of their lands. Fraser showed an early interest in art, especially sculpturing, after witnessing a man in Mitchell carving in chalkstone.

After his family moved to Chicago, a 13-year-old Fraser began studying at the Art Institute. In 1893, at the age of 17, he was able to assist in the sculpture installations at the World’s Fair. When he saw depictions of Native Americans in the sculptures there, it renewed his interest in producing an image himself.

In 1897 his father allowed his son to travel to Paris to further his art studies. Soon afterwards, the young Fraser produced an 18-inch bronze of the End of the Trail, where he was awarded a prize at the American Artists Association exhibition in Paris. This award allowed Fraser to study at the Beaux Arts School in Paris, where he was influenced by the work of Michelangelo and saw the works of the Renaissance master in person during a trip to Italy.

When Fraser returned to the United States in 1900, he began sculpting in bronze and plaster, conveying the emotions he saw in Michelangelo’s work. He received his first commission in 1901, the Saint-Gaudens Medal, created for the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York; a piece that honored his mentor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, a prolific sculptor in his own right. That piece led to the monumental sculpture of The End of Trail, created for the 1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, California, based on his original bronze sculpture.

About the Sculpture

The iconic End of The Trail was cast in plaster and stood approximately 17 feet tall. At the fair It was juxtaposed with the Pioneer Mother, which was a celebration of the American pioneer and fit with the larger narrative of the fair, which was conquest and expansionism. The exposition’s artwork very much celebrated the triumph of American and European civilization over the ingenious people of the Americas. The official narrative glorified the ideals of progress and social sciences and reinforced the vanishing race ideology. In the late 1800s and early 1900s Americans believed that Native Americans were doomed to vanish, and their culture would eventually cease to exist. The End of the Trail very much supported that narrative, even though that was not the intention of James Fraser. Even scholars have acknowledged that this narrative from the expedition was not true.

By 1915 the idea of the vanishing savage race discourse was being replaced with the idea of a doomed, but noble race of Native Americans. This allows us to differentiate between the conquered people that was celebrated at previous fairs, to the doomed first Americans at the Panama Pacific International Exposition. In 1915 the reality is that Native Americans were not looking to the past but grappling with the progressive era of current life.

At the conclusion of the exposition, The End of the Trail floundered in a graveyard of statues and was finally purchased in 1919 by Tulare County in California’s Central Valley and was erected at Mooney Grove Park. Over the years, the sculpture slowly deteriorated due to its exposure to the elements. Then, in 1968 it was acquired by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma and restored.

Shortly after The End of the Trail was shown in 1915, reproductions appeared for sale in the form of prints and photographs. Even today, this icon of sculpture has been created on postcards, T-shirts, cups, lamps, and clocks, to name a few. The image even graced the cover of a Beach Boys album in 1971. Many believe this trivializes the sculpture’s meaning, the disappearing of the Native American way of life. In many ways, Fraser’s personal legacy still resonates with Americans, as it did in the early part of the 20th century.

At Southwest Arts and Design we continue to embrace The End of the Trail’s legacy through oil paintings, velvet paintings, and on Native American inspired symbols such as hand painted mandalas, wood painted mandalas, hand painted velvet shields, leather star shields, hand painted canvas shields, wood painted shields, painted rattles, and velvet dream catcher shields.